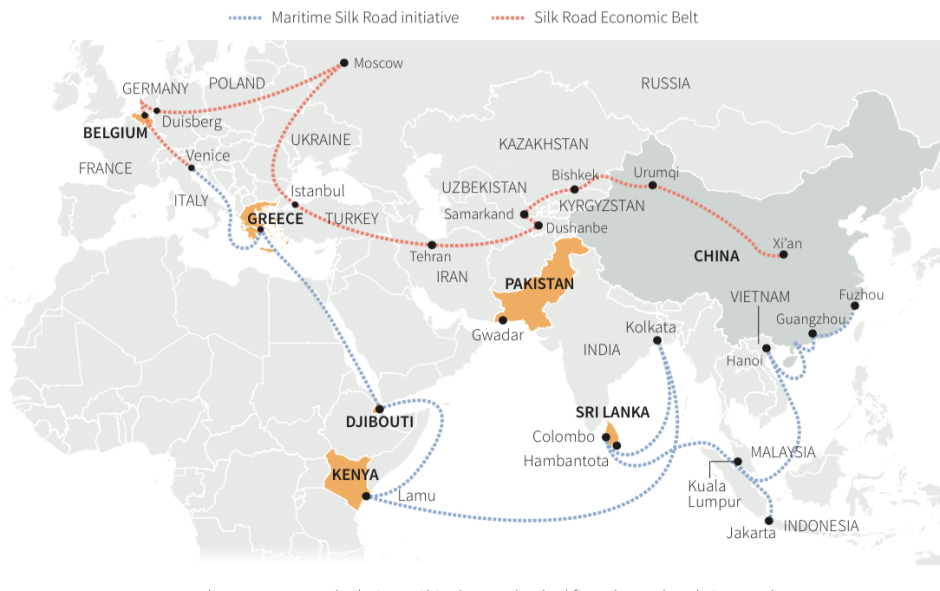

PRESIDENT Xi Jinping of China is hard selling the most ambitious infrastructure project the world would ever see. Named the One Belt and One Road Initiative (OBOR), the project comprises a series of ports, pipelines, power stations, railways and roads to secure and expand China’s trade links to the world, covering at 65 countries. The name conjures romantic imagery of camels carrying silks through the desert, based on the old Silk Road that exported silks to Europe. As populist nationalist movements have gained traction in the West, Jinping has eyed an opportunity to gain influence in the world order by preaching the rewards of revitalising globalisation. OBOR is an opportunity to take advantage of the US’ retreating influence under Donald Trump’s presidency.

Evaluating the benefits of OBOR are incredibly difficult. The world’s second largest project, the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe after the Second World War, only had a current-day value of $103bn. Estimated to cost around $1 trillion, OBOR is 10 times the size and encompasses far more countries with far more diversely structured economies than postwar Western Europe. Measures of the financial gain to China, therefore, are unlikely to be accurate, but the chief economic benefits come in the form of greater access to foreign markets. This creates opportunities for export-led growth and greater certainty and security of raw material supplies. Having invested heavily in high-tech industry, OBOR would stand China in good stead to support its manufacturing base.

OBOR also offers a solution to geopolitical issues. The highly contended South China Sea has long been a strategic headache for China: for its ships to reach the rest of the world, they pass by a multitude of countries, including Japan, the Korean peninsula and Vietnam. Were these powers to blockade China’s maritime access to the world, China would be unable to export, the very thing it built its success on as capitalist economy and a huge threat to its continued growth. The Pakistani city of Gwadar offers a solution to this. Pakistan borders south-western China and has access to the Arabian Sea, which provides China with an alternative route out to sea and is why a state-owned Chinese company signed a 40-year lease on a port there.

Infrastructure projects in foreign countries entwines China tighter into the global economy and they become a much larger player in the world. This is especially true now that the US has withdrawn from the Transatlantic Trade Partnership, a trade deal between countries in the Pacific region, and that Donald Trump is somewhat considered a joke in the West. Interdependent blocs of countries are far less prone to conflicts and more open to co-operation, so OBOR stands to hand greater power to the Communist Party for use in future conflicts.

China is using its big state-owned banks to provide financing for other countries, including developing countries with weak credit ratings such as Djibouti. Earlier this year, a railway – built and financed by China, of course – opened between Djibouti and Addis Ababa in Ethiopia. Although Djibouti is enjoying steady economic growth of 6.7%, its government lacks transparency, its debts have hit 60% of GDP, the IMF puts unemployment at 39% and almost 1 in 4 live in extreme poverty. Should the project fail to bolster growth, or adverse economic conditions batter growth, Djibouti will find itself in hot water with the Chinese – little is known about the terms of the loans or how their creditors will use their leverage.

What is clear is that China is taking a gamble. Chinese government debt relative to the size of their economy has risen sharply, rising almost 20 percentage points since the Global Financial Crash. Total debt, including household, government and corporate debt, has risen by 100 percentage points in just as long. If OBOR cannot kickstart slowing growth, then OBOR fuelling a pile-up of debt risks a 2008 US-style financial crash or an extended struggle with deflation and low growth, as happened in Japan. Not only this, but China has a poor track record of cost-effective infrastructure construction. If previous builds, such as a railway in Kenya that was four times more expensive than the international average, then spending will vastly exceed the initial budget. But if the net economic benefits are uncertain – and moreover, the benefits of a better spot in the international pecking order – then why is Xinping pushing OBOR so hard?

One must consider that as well as factors pulling China to OBOR, there are push factors. Growth has slowed in recent years. It is steady, but the people of China have come to expect living standards to always be on the up. Whilst they rapidly become better off, they may tolerate the more unsavoury aspects of being ruled by the Communist Party: a democratic deficit, a poor human rights record. But if life stopped improving, why should they continue to tolerate such governance?

A sufficiently large enough spark could create enough civil discourse for regions of China to break away and declare independence. Tibet is the most likely territory to break, but Xinjiang is strategically the most crucial. It borders eight countries and is China’s land access point to the rest of the continent – without it, China would depend heavily on the South China Sea, which would only lead to greater tensions. Not only could OBOR help postpone a slowdown in growth and buy the Communist Party time to find the next growth cure, but OBOR helps anchor Xinjiang to China, quelling future independence movements.

It soon becomes obvious that OBOR is driven by the state, rather than commerce. The initiative is economically risky and could end in financial meltdown, but if pulled off successfully, it presents an excellent vehicle to heighten China’s standing in the world order. Given previous projects, the initiative is highly likely to go far over budget and it is unclear whether it will see full fruition, especially as it requires so many deals to be struck. Having peddled the dream so openly, the full virtue of soft power will come from completion, but the more individual projects completed, the closer China gets to financial ruin and egg on their proverbial international face. Jinping faces quite the balancing act.

Credit: Featured Image via Reuters